Ansible Service Account Guidelines

Categories:

Problem

In environments transitioning to automation, such as Dutch government entities, teams accustomed to manual lifecycle management (LCM) and maintenance are often reluctant to grant broad access. This hesitation leads to struggles in defining permissions for Ansible service accounts. Organizations also face uncertainty about the number of service accounts to create—one shared account or multiple—and how to assign permissions. Favoring restricted sudo rules on Linux or JEA on Windows, teams aim to limit access. However, overly restrictive permissions can hinder automation, creating logical contradictions and undermining the benefits of IaC and GitOps.

Context

In environments starting with Ansible for automation, engineers traditionally perform tasks manually on systems. With manual LCM and maintenance, there is heightened awareness that accounts, including service accounts, often have overly broad permissions. These concerns extend to Ansible service accounts, prompting questions about the number of accounts and their privileges, especially in multi-team setups. Without automation, implementing and enforcing PoLP and JEA is challenging. The principle of least privilege (PoLP) is desirable but requires careful design to avoid chaos, high costs, and frustration. Logical inconsistencies arise when restricting Ansible prevents it from automating its own constraints, such as JEA configurations.

Solution

Adopt a phased approach to Ansible service accounts, starting with broader access to ensure usability and progressively applying PoLP as automation matures. Use elementary logic to evaluate restrictions and emphasize IaC/GitOps as inherent risk mitigators. A key concept is the team service account, treating it as an “extra team member” named Ansible. This aligns with DevOps principles of self-organization, responsibility, and delegating maintenance to automation, even if it feels counterintuitive at first1.

Phase 1: Start with Admin/Root Access and Account Setup

- Grant the Ansible service account full admin/root privileges on Windows and Linux hosts. This enables complete automation without immediate barriers.

- Risks are mitigated through IaC and GitOps: Changes are codified in an inventory project, reviewed via merge requests, and applied idempotently. No direct human access reduces errors and unauthorized changes.

- Avoid the logical fallacy of restricting Ansible to the point of undermining IaC usability. For example, if JEA limits Ansible, manual intervention is needed for JEA setup, contradicting automation goals2.

- For organizations with multiple teams, start by providing each team with its

own account. Decide thoughtfully between one shared account or per-team

accounts. Prioritize team service accounts as a key concept in DevOps,

where the team is central to self-organization and responsibility. Treat

the team’s service account as an “extra team member” named Ansible,

delegating maintenance to automation. This might seem counterintuitive at

first, as instincts often lean toward per-service accounts, but it aligns

logically with collaborative DevOps principles1.

- Collaborative Single Account: Teams can share one account if engineering and operations are collaborative across teams. This fosters collaboration in a single inventory project.

- Per-Team Accounts: Preferable if teams manage distinct services. Create one service account per team, using Active Directory (AD) groups to delegate permissions. Nest service-specific groups into team groups for inheritance.

- In mature setups, give Ansible expanded access (e.g., root across all environments) while limiting human access.

Phase 2: Introduce PoLP

- Apply PoLP thoughtfully, not blindly. As your organization matures in automation, design restrictions for team Ansible service accounts based on a careful policy that prioritizes logic and security.

- Policy Design: Develop a clear policy outlining when and how to restrict accounts. For instance, restrictions should only be applied after broad access has enabled full automation maturity. Focus on per-team accounts in multi-team environments, limiting them to specific services or environments they manage. Use tools like sudo rules on Linux or JEA on Windows to grant just enough privileges for required tasks.

- Elementary Logic in Restrictions: Ensure restrictions follow logical principles. For example, it does not make sense to restrict the Ansible service account’s permissions to be less than those of team members' accounts, as the service account operates in a more secure, auditable manner via IaC and GitOps3. Prioritize securing human accounts first, then refine service accounts.

- Implementation Steps:

- Assess current automation workflows to identify minimal required permissions.

- Test restrictions in non-production environments using inventory projects to avoid disrupting operations.

- Regularly review and update the policy as automation evolves, ensuring it aligns with organizational security goals without hindering efficiency.

Benefits

- Risk Mitigation: IaC and GitOps limit human errors, making broad access safer than manual methods.

- Usability: Avoids frustration from restrictive setups that break automation.

- Scalability: Phased approach supports DevOps transitions, with logic-based decisions preventing costly mistakes.

- Collaboration: Per-team or shared accounts enable efficient multi-team workflows.

Alternatives (Optional)

- Strict PoLP from the Start: Viable in highly regulated environments but may require additional tools (e.g., SELinux) and initial manual setups, increasing costs.

- Per-Service Accounts: Leads to sprawl in large organizations; use only for high isolation needs.

Examples and Implementation

Phase 1: Per-Team Account Setup

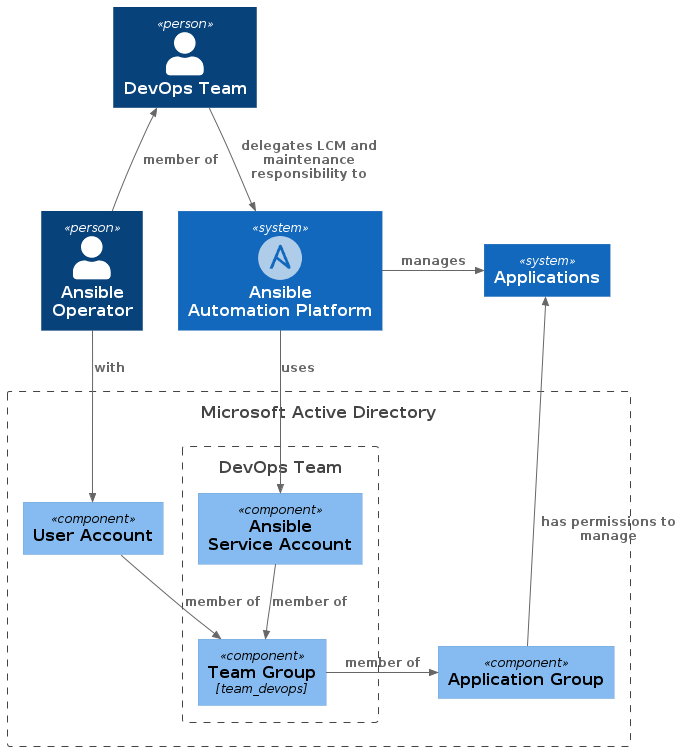

This diagram illustrates the structure for managing service accounts in a team setting. It treats the Ansible Automation Platform (AAP) as an integral team member within a DevOps team:

- AAP takes center stage in automation efforts, functioning like an additional team member that handles lifecycle management (LCM) and maintenance tasks.

- To support this, the DevOps team is assigned its own group in Microsoft Active Directory (AD), with an Ansible service account added as a member of this team group.

- This ensures that all team members, including the Ansible service account, receive identical permissions through group inheritance, promoting consistency and collaboration.

- It also supports DevOps, Agile, and Scrum principles by fostering equal

access, shared responsibility, and efficient automation workflows.

Phase 2: Introducing PoLP

In phase two, introduce PoLP by following rules of elementary logic: begin restricting user accounts first, rather than the Ansible service account. For example, Ansible engineers might only need access to development, whereas Ansible operators need access to test, acceptance, and production as well.

Focus on human accounts to align with the logical premise that service accounts operate more securely via IaC and GitOps. Use AD groups to enforce these restrictions, ensuring the Ansible service account retains sufficient privileges to automate configurations without manual intervention. Test these restrictions in a non-production environment to validate logic and avoid disruptions.

Using elementary logic, we can evaluate why a team service account is conceptually sound, even if counterintuitive:

- Premises:

- P1: DevOps emphasizes self-organizing teams taking responsibility for their services, including automation.

- P2: Ansible acts as an automated “team member” handling maintenance tasks idempotently via IaC and GitOps.

- P3: Per-service accounts fragment responsibility and increase management overhead.

- P4: Instincts favor per-service granularity, but this overlooks team cohesion in DevOps.

- Reasoning: From P1 and P2, the service account should align with team structure, inheriting team-level permissions (e.g., via AD groups). P3 shows fragmentation hinders collaboration, while P4 highlights a common bias toward over-restriction.

- Conclusion: A team service account promotes DevOps principles by enabling unified, auditable automation within the team, reducing sprawl and enhancing efficiency.

- Premises:

Using elementary logic, we can analyze the contradiction in restricting Ansible for JEA configuration:

- Premises:

- P1: Automate everything with Ansible, including JEA on Windows.

- P2: JEA requires admin rights and complex steps on each server.

- P3: Ansible needs admin rights to configure JEA.

- P4: If Ansible is restricted by JEA (PoLP), it can’t exercise admin rights freely.

- Reasoning: From P1 and P2, Ansible must have admin rights (P3). But P4 creates a chicken-egg problem: Ansible needs JEA to access but can’t configure JEA without access.

- Conclusion: Restricting Ansible forces manual steps, undermining P1. Thus, exempt Ansible from JEA and grant it admin rights for full automation.

- Premises:

Using elementary logic, it is not sensible to restrict permissions of the Ansible service account first, rather than the team member user accounts:

- Premises:

- P1: Ansible service accounts operate via audited, idempotent IaC and GitOps processes, reducing human error and unauthorized changes.

- P2: Team member accounts involve direct human access, increasing risks of mistakes or misuse.

- P3: Restricting the service account below team member levels creates inconsistencies, as the account is inherently more secure.

- Reasoning: From P1 and P2, prioritize securing human accounts (P3). The service account’s controlled nature makes it safer for broader access.

- Conclusion: Focus restrictions on team member accounts first to enhance security without illogical constraints on automation tools.

- Premises:

Feedback

Was this page helpful?

Glad to hear it! Please tell us how we can improve.

Sorry to hear that. Please tell us how we can improve.